Exclusive THE SUNDAY EXPRESS (London) 7/29/07

(Click Diana)

Previous brushes with fame.....

Carrie Hamilton

Bill Youngblood Photography

Bill Youngblood PhotographyIn March 2007 actress/comedienne

Carol Burnett and Los Angeles painter Louis Briel unveiled Briel’s new portrait of Burnett’s daughter, Carrie Hamilton, an actor, playwright, screenwriter, singer/songwriter and musician, who died of cancer in 2002 at age 38.

"As far as I'm concerned, Louis captured Carrie's smile, which was one in a million. I'm grateful to him for his dedication and his obvious love of her humor and grace. It's a joy for me, as her Mom, to behold," Burnett said.

The painting was presented at a gala party in San Marino hosted by Lilah Stangeland and Greg Stone and now hangs in the lobby of the newly named Carrie Hamilton Theatre at the Pasadena Playhouse.

"When I heard that the Balcony Theatre at the Pasadena Playhouse was being renamed to honor Carrie Hamilton, I began reading and learning about Carrie. Obviously, she inherited the splendid strength and abundant talent of her mother, Carol Burnett, and in her much too brief span of years, she made a profound impact on those who came to love and admire her. For many people, Carrie became the exclamation point at the end the sentence.

I decided I wanted to paint Carrie, to capture the warmth and generosity of this special young woman, as a gift for Carol and the Pasadena Playhouse. Because I insist on getting to know the story I'm putting on canvas, I knew I couldn’t do it without Carol’s help. My heart has to be in it – otherwise, it's just window dressing. So, with Carol as my gentle guide, I painted Carrie’s portrait, while Carrie’s exuberant spirit held my hand and guided my brush through the details.

Painting portraits is a calling for me. It helped soothe the loneliness I felt as an only child, and it has helped me survive the losses I’ve suffered as an adult. In doing posthumous portraits, I’ve learned that my gift can help others, too. While a portrait cannot replace those we lose, it can serve as a compassionate bridge to the future, and rather than sadness, there is always abundant joy in the journey."

Louis Briel

Los Angeles

“Golly, Mr. Kent”“Oooh, it is so very much Jack,” she said.

Leslie Caron was standing in front of my portrait of Jack Larson at the O’Melveny Gallery on Melrose.

“And Dewy. He is so beautiful. Oooh, it is perfect.”

Leslie had come with Jack to the opening. Ted Casablanca, paying rapt attention, would have his blurb for the week’s column. My old friend Scott was there, visiting me from Boston. I thanked Leslie for her compliment. It all felt great, a fine night, good LA chemistry.

I met Jack Larson by accident in 1998 at the Louver Gallery in Venice, where David Hockney was having a show. Jack, who played the irrepressible “Youth in Peril” Jimmy Olsen in the hit 50’s TV Superman, with George Reeves, was familiar to me from recent interviews on TV. He was surrounded by a group, chatting, dressed in his now rumpled, still tweedy, best Jimmy Olsen outfit. I leaned over to my friend Howard and said, a little too loud, “Look, there’s Jimmy Olsen!” Jack looked over and grinned. I was caught.

A little later, red-faced, I sidled up to Jack. “Mr. Larson, I hope I didn’t embarrass you.”

“Not a bit. It’s when they don’t notice! So, who are you?”

“An artist, a painter, just moved here from Virginia.”

“I’d like to see your work. Maybe we can meet for an ice cream soda,” Jack said with a wink.

“An ice cream soda,” imagine that. I liked him already.

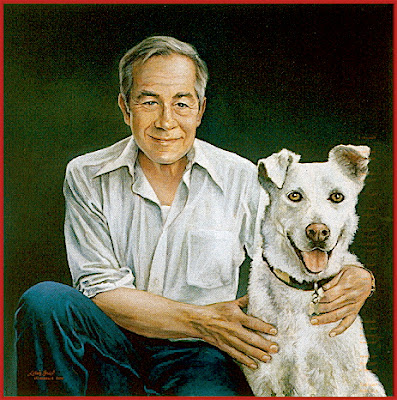

We met for the soda. Jack looked at my portfolio, and we began a friendship, which I commemorated that night with the unveiling of my portrait of Jack and Dewy, his best canine confidant and companion.

Jack's been very generous with his time and interest in my work. He’s shared wonderful stories of growing up in LA and his life in Hollywood. He's a wonderfully accomplished man - as an actor, a producer, a librettist for opera, and does important philanthropic work through the James Bridges Foundation.

As I’ve gotten to know him better, I realize he’s emotionally very private, very old school. Storytelling is his best defense. It’s hard to know him well.

My guess is that Jack would not have consented to be painted, had I not suggested including Dewy. Dewy was the secret, the key to Jack’s heart, the key to a good painting.

I like to paint intimacy, vulnerability. It’s really hard to pretend with a dog. The photos I took to work from were pictures of a guy playing with his dog, a big kid, playing with his dog.

I’ll bet Dewy, an irrepressible “Dog in Peril”, thinks Jack is Superman.

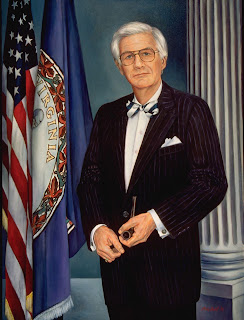

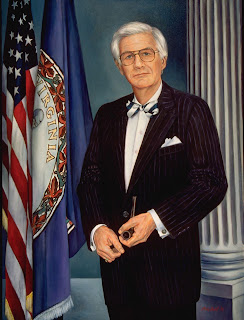

Portrait of a Gentleman

In 1992-1993 I painted tennis great

Arthur Ashe, shortly before his death from AIDS. I had known Arthur casually for several years through Virginia Heroes, a mentorship program for at-risk kids he had begun in Richmond. The unexpected combination of white shirt, tie and racquet is symbolically correct to describe this chapter, the last, of Arthur Ashe’s life - on the lecture circuit to promote the causes in which he believed, in a hurry, yet serene, always supported by the acclaim from his tennis days. The design of the painting is squared up - straight on - direct - like Arthur Ashe. The painting, now in the collection of the Smithsonian at the National Portrait Gallery, is the portrait of a gentleman.

Louis Briel, 1993

A Walk on the Right Wing

My closer friends kept asking how I had come to paint

Congressman Tom Bliley R-VA, for his Committee Room in the Rayburn Building of the House of Representatives. I wondered, too, how this had happened, since I always considered myself such an essential Democrat.

The Congressman and I kept it simple and did not talk politics. Despite our differences, I think Tom Bliley was a good representative for his home community, and as we worked together, I came to like him a lot. He is a gentleman. He’s thoughtful, and I appreciated his time and the respect he showed me, as I did my best to get his portrait right. The portrait is very right, I think, for the man and for the setting. I painted it all - the pinstripes, the flags and his pipe - a nod to unblinking support of tobacco. Even the twang of his accent is lurking somewhere under the brushstrokes.

I knew I had succeeded, when Mrs. Bliley came to see the painting. As the Congressman stood next to the easel, she exclaimed, “My Gawd, there are two of them!”

Someone yelled, “Did you hear about the President?"

It broke my heart when President Kennedy was murdered. I still remember how I felt on November 22, 1963, during my sophomore year at Hampden-Sydney College as I walked toward my dorm room. Back home in Richmond over Christmas break, I filled my emptiness and despair with a painting of the President, done from a NEWSWEEK cover.

I painted out my tears.

The following Spring I got my chance to be famous for fifteen minutes, even before Andy Warhol thought it up.

College President Taylor Reveley stopped me on campus one morning and told me

Robert Kennedy was making a trip to Prince Edward County to accept pennies Black school children had collected for the Kennedy Library. “I’d like to get him to the campus to address the student body,” Dr. Reveley said. But he needed bait. My painting of JFK, then hanging in my dorm room, was to be the bait, if I would agree to give it away. I was thrilled that I would have the chance to meet the President’s brother and give him my painting. “Absolutely, I’ll do it!”

Dr. Reveley phoned the Attorney General’s office. Yes. Robert Kennedy would gladly accept the painting. All morning long — it was May 11, 1964 — secret service men combed the campus. At last, amid the squirrels and 200-year-old oaks, the whir of helicopter blades began cutting the fragrant air, announcing Mr. Kennedy’s arrival. I suspect no helicopter had landed at Hampden-Sydney before then. The Attorney General briskly strode to Middlecourt, the President’s House, then back down the steps, toward Johns Auditorium where he was to deliver his talk.

Hampden-Sydney students were a conservative bunch and began to hiss and grumble when the Attorney General stepped up to the lectern. Sensing immediately that he was in enemy territory, Mr. Kennedy took off his jacket, rolled up his sleeves, put aside his prepared remarks, and said, “I believe you gentlemen may have a few questions”, whereupon he proceeded to field queries from a mostly hostile audience for forty-five minutes. With a combination of grace, courage, candor and humor, he won over the assembly, to receive a lengthy standing ovation.

Next he strode through a sea of handshakes to make me a celebrity. It worked. Bobby and Ethel made their way to the spot where I was standing - waiting, nervous, my painting in front of me, ready for my close up. As he approached, he reached for my right hand. He looked at me directly and said, “Very nice, very nice." I was thrilled. I couldn't believe this was really happening. Then I heard someone say, “Could you let us take a few pictures?” There we stood, Bobby Kennedy and I, both holding that painting I had done. Ethel was smiling and kept asking me what seemed to be a thousand questions. I said something in response, I’m sure. My life felt complete. Then he and Ethel boarded the helicopter and took my painting back to Washington. In a few weeks, Bobby Kennedy sent me a prompt and personal thank you note.

When my portrait of President Kennedy left my guardianship on a spring day in 1964, I felt reassured it would have a fortunate history. In our brief conversation, Bobby Kennedy told me he envisioned a section for commemorative artwork in the yet to be constructed Kennedy Library, and he would see to it that my painting found a home there.

After Bobby Kennedy’s murder in June of 1968, I wasn’t so sure. I knew his intentions about everything were no longer operative, but my life was busy, and I put thoughts about the painting away. Early in 1994, curiosity won out, and I began an inquiry to see if I could determine what had happened to the portrait.

First I called the Kennedy Library and spoke with Dave Powers, President Kennedy’s old friend and special assistant, who was the chief curator. We had a pleasant chat, but he told me he knew nothing of the painting. He suggested that I contact Ethel Kennedy to see if she could shed any light on its whereabouts. I wrote Mrs. Kennedy, and after waiting about six months for a reply, I called my old Harvard grad school chum Doris Kearns Goodwin to get her suggestions. She proposed that I write Congressman Joe Kennedy. Early in November 1995, I received a warm reply from Congressman Kennedy telling me he had spoken to his mother and Frank Rigg, by then the Museum Curator, and could learn nothing helpful. At the end of his letter, he appended a handwritten note:

“Louis - Many thanks for the beautiful painting. As I am sure you may understand, those were very turbulent times and many, many things and remembrances have been lost or stolen. But the spirit of your work and theirs goes on. Many thanks, Joe”

“Lost or Stolen” — those words intrigue me.

Someone, somewhere, knows the secret. The painting has had its journey and I suspect has an interesting tale to tell. Whatever the answer, I made a deal over a handshake one spring day in 1964 to let Robert Kennedy become the caretaker of my painting. Just as he was unable to safeguard himself or his legacy, he was unable to protect my painting, as he had hoped. I made the deal that day to let go, and all the love and effort and tears that went into the painting went along with it, indelibly couched in the paint.

And “The spirit of our work goes on.”

(WATCH THE PRESENTATION)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYW79fgHLE0&eurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.hsc.edu%2Fstories%2F&feature=player_embeddedLouis Briel, 2002

Dear Louis,

Dear Louis,